Art

Snap

S. Miller

Interview

Madison Butler, a.k.a. Blue-Haired Unicorn, is a start-up maven, builder of inclusive cultures, and “queer and Black AF.” She currently lives in Texas.

How long have you lived in Texas?

I have been in Texas for just under 4 years. I moved here October, 2017.

How would you describe Texas to people who don’t live there?

Ooof, that's a hard one. Texas is great and terrible all at the same time. There are parts of the culture of Austin that I love, but they're slowly starting to fade out as tech booms. However, Texas is still Texas. It has been a great career move for me, but I have experienced many instances of racism, homophobia, and misogyny here.

What are your favorite things about Texas?

The weather. I moved here to escape the cold New England winters.

Least favorite thing?

GREGORY ABBOTT.

What was your first thought when you heard about Texas Senate Bill 8, also known as the Texas Heartbeat Act?

My heart sat in my throat. As someone who has had two abortions that saved my life, I know how dangerous this bill is. This bill doesn't stop abortions, it stops the safe ones. Those who have the privilege to leave the state of Texas will still have access to abortions, while those who do not have the means to cross state lines will resort to at-home abortions or forced pregnancies.

I’m aware that talking about abortion can be political, dangerous, and personal. Please share any thoughts about or experiences with abortion that you’d care to.

Feel free to reference this post I made on LinkedIn.

It got over 100k views and the comments are absolutely BANANAS.

Sharing your experiences on LinkedIn was bold. What prompted you to make the post, and, beyond the bananas comments (which really are a LOT) have there been any ramifications?

I post fairly vulnerable content often, because I think it's important to talk about the things that make others uncomfortable, especially when they are other people's truths.

LinkedIn reached out to apologize for the wildness of the comments, and confirmed they were deleting any that went against their Terms of Service.

What do you think of Section 171.202 (3) of the Act, which states “Texas has compelling interests from the outset of a woman’s pregnancy in protecting the health of the woman and the life of the unborn child.”

Texas does not care about women's bodies. Texas cares about carrying out a religion that does not govern our country. They do not care about children, pregnancy or women—they care about control, and that control being handled and led by men. I grew up in a fundamentalist Christian church, and it feels like Texas is just one big version of that experience. They treat women as things to be owned, controlled, and tamed, rather than living beings with freedom to exist autonomously.

Section 171.208 of the Act makes it lawful for “any person” other than employees or officers of Texas governments to sue “any person” who performs or induces an abortion, aids or abets an abortion, or intends to aid or abet an abortion. How how does this new capacity to sue or be sued feel?

It's wild to me. We are creating bounty hunters out of regular citizens in the same breath that we legalized unlicensed right to carry. [Editor’s note: This a reference to a recent Texas law allowing people to carry handguns without a permit.] This is dangerous for women, period. Giving the public the ability to report women and anyone who helps them is incredibly harmful.

Have you changed anything in your life because of Texas Senate Bill 8? Will you?

I immediately started shopping for homes in New England. Although I will not be moving out of Texas at this time, I will likely start to spend less time here, and realistically, I wanted an escape plan in case things blow up in the 2022 or 2024 election. As a Black, queer woman I do not feel that Texas is safe for me any more. I live right outside of Austin in a lakeside town, and the commentary around this bill, COVID, and racism in America is nauseating, but also terrifying. The racism that permeates the community where I live in is blatant and unforgiving. I recently had a man threaten to spit on me, followed by another man who told me to "come clean his shit for china wages." Texas, even Austin, is not the "best country in America” that Texans paint it to be. Texas is run by a government that refuses to see past their own reflection in the mirror.

Is there anything in particular you’d like people outside of Texas to know right now? Is there anything you’d like people outside of Texas to do?

Vote. This could happen in any of our states if we do not pay attention to who is running and what they stand for. We cannot allow another presidency like 2016-2020, or governors like Abbott, to control the decisions of women.

Interview

This interviewee lived in Texas from 1992 to 1998.

How would you describe Texas to people who don’t live there?

Like a whole ‘nother country. Equally as friendly as it is backwards.

What are your favorite things about Texas?

Food, music, art, and Barton creek.

Least favorite?

Trucks, long commutes, Republicans, heat, Christians, and water bugs.

What was your first thought when you heard about Texas Senate Bill 8, also known as the Texas Heartbeat Act?

No way.

I’m aware that talking about abortion can be political, dangerous, and personal. Please share any thoughts about or experiences with abortion that you’d care to.

I had an abortion, in Texas, in 1994. I had to walk past protesters shouting, and really graphic signage on the way out. I’m extremely grateful that it was legal and accessible at the time.

It wasn’t an easy decision, but it was the right one.

Then we went for muffuletta and I threw up in the parking lot.

What do you think of Section 171.202 (3) of the Act, which states “Texas has compelling interests from the outset of a woman’s pregnancy in protecting the health of the woman and the life of the unborn child.”

“Compelling interests” to continue the patriarchy, and to keep women down—especially underserved women.

Section 171.208 of the Act makes it lawful for “any person” other than employees or officers of Texas governments to sue “any person” who performs or induces an abortion, aids or abets an abortion, or intends to aid or abet an abortion. How how does this new capacity to sue or be sued feel?

Seems like it’d feel great for for-profit lawyers and vigilantism, but terrible for women and health care workers.

Have you changed anything in your life because of Texas Senate Bill 8? Will you?

Yes. I’ve got more dollars and time for Planned Parenthood.

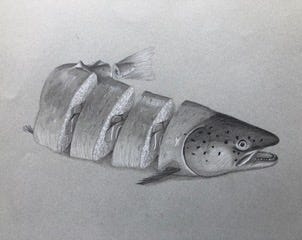

Art

Untitled

E. Grove

Recollection

Fish

A Woman

I found out I was pregnant. It was an accident. And though I was amazed that I was capable of a miracle, there's things I had begun to do, that I wanted to finish. Things that would take many years to finish, if at all, if I stopped to have a baby.

Still, it was hard to decide. My husband left it up to me. I thought it was because he had no idea what to do, either. He was patient, especially since I kept changing my mind every two hours. I wanted to be fair to me, and to It. Of course, It hasn't even evolved past amphibian yet, so maybe I didn’t need to be fair to It. I worried that this line of reasoning was arrogant. Of course, at that point, It was just a fish. I had no problem with killing fish.

My grandfather died the same day I found out I was pregnant. I felt spooked. Was it nothing more than a coincidence? Was this fish connected to him somehow, and saying ‘no’ to it was like saying ‘no’ to a bigger, more powerful thing, so big and powerful that I could only know a small piece, from my limited vantage point? Did It got tired of waiting for me to be ready? It took matters into its own hands.

During World War II, my grandfather contracted a rare tropical virus while serving in the Pacific. The virus caused his brain’s reservoirs of fluid to overflow. His brain was drowning. They installed a pump inside his skull. This caused a great deal of pain for the next fifty years but stopped the drowning.

A few days prior to his death, my grandfather decided he didn’t want to live any longer, so he stopped eating. He lived in a wretched nursing home that my mother explained was the only option. He was blind, he couldn’t walk, and he was on very strong painkillers.

The last time I saw him, we held hands. He gripped my hand very tightly, as if he was pleading with me.

My grandfather controlled his life by deciding not to continue. Could I control this birth, by my own measure, as well? Was it true that whatever happens was meant to happen?

I went along for a while this way, chasing philosophical questions. But if I stood up too quickly—then I could feel It. The fish. The cramps were like a tightness, an embroiling. Like the fish was blowing bubbles. It was blowing bubbles hard, at me.

I made up my mind finally, and thought I felt good about my decision. I made an appointment with the doctor. I showed up on time. I was alone in the waiting room. The painted wall opposite was chipped. Plastic mauve flowers from Pic n’ Save crouched in the corner, forlorn and dusty, huddled in a black vase on a square pedestal. I avoided eye contact with the magazines to my left: Pregnancy and You. Parenting. A pile of children's books placed to my right looked at me askance, with hands on hips.

The nurse led me into an examining room. I changed and sat on the edge of a high table wearing a medical privacy gown made of paper.

I had to wait a long time in the room, perched on the table, under the scratchy paper gown that kept sliding off my person unless I held it in place. A large trolley with a tray of instruments hiding under a sheet kept me company. I figured all that equipment under the sheet must be for the termination.

That's what the doctor liked to call it—termination.

As I waited (too long), one sentence kept going through my head. “The reasons aren't compelling enough. They aren't compelling enough. They aren't compelling. Not compelling. They aren't compelling enough.”

Fighting Bork’s nomination to the Supreme Court, I had marched with WAC—Women's Action Coalition. I had chanted, “keep your rosaries off my ovaries.” I still believed what I believed. But something had shifted.

When the doctor came in and said, “Good, you made up your mind quickly, that's good,” I looked at her and said, "I thought I had, I thought I was sure, but now, but now I'm not sure.” I started to cry.

She thought that comfort came from many words. She went on about the pros and cons, and how it isn't easy to decide, and as she talked, it gave me time to think. She talked and talked without asking me anything.

I reviewed my favorite fantasy. In the fantasy, I am asked to do something alluring and important, and I say no. In one version, I am offered the presidency. I say in response, “What a great honor. But no, I don't feel like it.” In another, I might be a teenage Lana Turner in Schwab's drugstore. A bigshot producer swoops in and offers to make me a star. “How generous of you,” I say, gazing sympathetically into his cigar smoke, “But it's out of the question.” I smile, and go back to my milkshake. In each fantasy, the ultimate moment comes when I can say no.

The doctor was still talking. “I myself have only one child, but I came from a family of five. Yes! Five children. My grandmother raised us. But for me, one is enough!”

I thought to myself, what am I doing? Here's my chance. My chance to say no. I don't know what happened. The car went off the cliff. It was bigger than me. It seemed wrong to say no to so much that's beyond my imagination. It seemed wrong to turn my back on a big part of life. So I thought, “You're still saying No. You're saying No to the No.”

And after that, I never doubted it again.

Two months later, I couldn’t fit into my jeans. I never puked in the morning but I got hungry every three hours and felt like shit more often than I felt fine.

I received over fifty pieces of contradictory advice from the pregnancy veterans. Wear a support girdle—they prevent stretch marks. Stretch marks are hereditary—you either get them or you don't. Eat saltines, it settles your stomach. Stay away from salt, you'll bloat so much you'll start to float. Give into whatever you feel like eating. Resist eating too much, and resist eating whatever you feel like. Pregnancy makes your skin look great. Pregnancy makes your skin break out.

I felt very relaxed. Hallmark cards made me cry. It must have been that thousand percent hormone level. I didn’t sweat the small things, and the big things didn’t seem that big. I felt like I was on a train. It was a slow train, that stops in every little town. As it meandered along, I could see each farm and field; every cow, horse, and tree. I had no idea where I was supposed to get off, but it wasn’t important. I knew I would eventually arrive, on time.

Recollection

I don’t usually tell this story.

C. Hudak

Standing outside the clinic beneath an unencumbered sun, I paused for what felt like a long, beautiful time, to let the joy flood through me.

I was no longer pregnant.

This seemed too good to be true.

That whole time was sunny.

First: the jarring transition from sparkling, late spring into the darkness of the Catholic health center to get a pregnancy test. Second: the sliding, sidewise light through the window in the tiny, gray exam room where the nurse told me yes, I was pregnant; yes, there was an excellent clinic that would give me an abortion very nearby; and please, don’t mention to anyone that she told me about the clinic since she was, technically, working at a Catholic institution. Third: the warm, flat sunlight washing over the lawn where my new boyfriend was playing catch with a friend.

I called him over.

“Guess what we can do?” I said. My boyfriend was very young, very new. At everything. I felt scared, and I felt guilty. Maybe I—older than he was, already a single mother—had somehow tainted him. The fear faded after my abortion, but the guilt didn’t dissolve until years later, when I heard that he co-established a local reproductive justice organization.

“We can make a baby.”

I honestly don’t remember what my young boyfriend thought or felt. He asked me what I would do. I told him I would get an abortion. I told him the nurse told me where I could get a good one, which felt oddly like having an insider’s recommendation for a good restaurant. He asked if I was scared. I said I was. He asked if I would like him to go with me. I said I would.

My daughter had recently celebrated her second birthday. I was her only parent, and I lived in the strange place some uppity, poor, single mothers live, where it feels like no matter our efforts, no matter the reality of our lives and work, our simple presence offends and upsets. This compounded my fear. When I nervously asked my nice, married, middle-class friend Atara* if she and her husband would watch my daughter while I went to have an abortion, she surprised me by whispering about her own abortion experiences.

Unlikely as it sounds, this was the first time it dawned on me, viscerally, that maybe I wasn’t the only one. Viscera: “organs of the digestive, respiratory, urogenital, and endocrine systems as well as the spleen, the heart, and great vessels.” I felt it in my body, all the way through my overfull uterus: other women had been in this place, even if not one had ever mentioned it to me before.

The day of the abortion, my boyfriend and I drove my daughter to Atara’s slightly suburban home, then returned to the city center. We had to drive around a bit, looking for parking. I wondered, as we walked to the clinic, whether it would be physically taxing to walk back to the car.

This clinic was not like the Planned Parenthoods of my late teens and early twenties, when—only wanting a goddamned pap smear—I was regularly confronted by old white men with huge bloody signs, shouting about baby killers. This clinic was beige and nondescript and I felt a little surprised when no one accosted us outside their doors. In the waiting room, I looked at every woman and couple and wondered whether any of them was there for the same reason we were.

The waiting room was bright and clean. No one chatted. It was very quiet.

When it was my turn, we went, first, into a book-lined office that had tall windows, a big wooden desk, and comfortable chairs. The head of the clinic, a woman not even old enough to be my mother, sat behind the desk. She asked to speak with me alone. She and I talked about my daughter, and about why I wanted an abortion. I asked her if I should be scared, and I asked if it would hurt.

Eventually, my boyfriend and I were returned to one another, and escorted into an exam room. The room was big and white. The overhead lights were mostly switched off—I remember watching the sunlight at the window and listening to the traffic outside. Above me, a mobile of modernist fish floated more and more floatily as the anti-anxiety medication did its work.

Nurses, assistants, the doctor all paraded purposefully in and out. First, there was an ultrasound. Remembering the ultrasounds from my first pregnancy, I imagined that black and gray screen and felt… disgusted. My body—still nursing, flooded with low-dose birth control pills—had betrayed me.

The doctor asked about my daughter. I have written poems about this part. During my abortion, I talked—and talked and talked—about my baby daughter. I talked about how strange and beautiful my baby was to me, how unexpected she was and how unexpected it was for her and I to be growing into the family we were just then beginning.

My abortion did not hurt. In the moments it pinched—like the worst bits of a pap smear—I squeezed my boyfriend’s hand. But I never stopped thinking or talking about my magnificent daughter.

And then, it was over. I was surprised how quickly things went. I rested in a bright, white, post-operative room. A gentle medical assistant chatted with me to determine whether I was ready to leave. I felt surrounded by beautiful, smart women who were committed to supporting me and my family. I felt as if I’d joined a very special, very excellent club.

And then there I was, standing outside in that stunning sun, overwhelmed with joyful relief.

While I was writing this, I learned that the clinic where I had my abortion and where, years later, I accompanied a young friend for hers, no longer exists. It has been incorporated into a larger entity, which now provides abortions across western Washington.

We’re lucky here in Washington, these days. In 1950, Washingtonians who sought abortions (regardless of whether they found them) were guilty of criminal behavior. In 1967, 24-year-old Raisa Trytiak died of an embolism “caused by a botched abortion.”[1] A month later, 22-year-old Elizabeth Zack Staley died after her husband and a friend attempted an ad hoc, at home abortion. Staley’s husband was sentenced to 15 years. [ibid.]

In 1973, Roe v. Wade protected the right to abortion across the United States, including in Washington state.

In 1991, the people of Washington decided Roe v. Wade was insufficient, and they voted to approve Initiative 120.[2] As a result, the Revised Code of Washington today reads:

The sovereign people hereby declare that every individual possesses a fundamental right of privacy with respect to personal reproductive decisions.

Accordingly, it is the public policy of the state of Washington that:

(1) Every individual has the fundamental right to choose or refuse birth control;

(2) Every woman has the fundamental right to choose or refuse to have an abortion, except as specifically limited by RCW 9.02.100 through 9.02.170 and 9.02.900 through 9.02.902;

(3) Except as specifically permitted by RCW 9.02.100 through 9.02.170 and 9.02.900 through 9.02.902, the state shall not deny or interfere with a woman's fundamental right to choose or refuse to have an abortion; and

(4) The state shall not discriminate against the exercise of these rights in the regulation or provision of benefits, facilities, services, or information.[3]

What this law provides is both the legal right to abortion, and the legal right to fair access to abortion. Regardless of age, marital status, or immigration status, Washingtonians have the right to abortion and access to resources to help them obtain abortions.[4] [5]

According to the Seattle Times, Initiative 120 was developed, in part, to counteract the conservatives of the Reagan era, and could protect Washingtonians’ rights to privacy and abortion in these new end times.[6]

* Name changed.

[1] http://depts.washington.edu/civilr/abortion_deaths.htm

[2] https://www.historylink.org/File/5313. You’ll want to read that whole story, as it includes a good bit about a woman heckling Washington lawmakers about their relative levels of intelligence.

[3] https://app.leg.wa.gov/RCW/default.aspx?cite=9.02.100

[4] https://www.doh.wa.gov/YouandYourFamily/SexualandReproductiveHealth/Abortion

[5] https://www.legalvoice.org/abortion-rights-washington

[6]https://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/health/what-would-a-conservative-supreme-court-mean-for-roe-v-wade-to-local-activists-its-history-repeating/

Art

Black and White

K. Hartmetz

Law

Explicit Bias: The Fifth Circuit’s Conservative Agenda

A Lawyer

The United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit has a well-deserved reputation as the most conservative of the thirteen federal courts of appeals. Based in New Orleans, and responsible for hearing appeals originating from Texas, Mississippi, and Louisiana, the Fifth Circuit routinely provides a friendly forum for conservative interest groups hoping to overturn progressive policies, promote the interests of big business, punish immigrants, undermine democracy, and otherwise impose right-wing values on the masses. Among a long list of radical decisions, the Fifth Circuit has invalidated the Affordable Care Act’s individual mandate, prevented the implementation of the Deferred Action for Parents of Americans program, affirmed racially discriminatory voting restrictions, reduced protections against double jeopardy, and denied Title VII protections to the LGBTQ community. Things are particularly bad in the Firth Circuit when it comes to women’s reproductive rights: the Fifth Circuit has repeatedly issued decisions restricting abortion rights that are so radical that the conservative-leaning Supreme Court has felt compelled to intervene.

An already bad situation became much worse during the Trump administration.

Perhaps the literal only thing the Trump administration did competently was fill judicial seats. Unfortunately, the administration was not merely competent; it was unprecedentedly efficient. The Trump administration filled 229 judicial vacancies in four years—more than had been filled in any presidential term since Congress expanded the federal judiciary in the 1970s. Nearly one-third of all active federal appellate judges are now Trump appointees.

Among the gems Trump appointed to the Fifth Circuit is Judge Stuart Kyle Duncan, who in his prior practice opposed same sex marriage before the Supreme Court and, upon losing, called the Supreme Court’s Obergefell decision an “abject failure” that “imperils civic peace” and “raises a question about the legitimacy of the court.” Among Judge Duncan’s radical actions since taking the bench: he wrote a decision granting mandamus—an extremely unusual step of intervening in a lower court proceeding—to uphold Texas Governor Greg Abbott’s executive order banning abortions during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Another Trump appointee, Judge James Ho—who, in a prior life, helped draft the legal memo the George W. Bush administration used to justify torture—has written multiple opinions calling on his Fifth Circuit colleagues to radically expand the concept of qualified immunity to protect police officers from any and all liability for the use of force, no matter how egregious. And he has written a concurring opinion calling abortion a “moral tragedy.”

The Trump administration not only filled open seats, but it strategically created openings to fill with more radical nominees. In 2018, Trump created an opening on the Fifth Circuit by selecting Judge Edward Prado—a relatively moderate George W. Bush appointee—to be the next U.S. Ambassador to Argentina. The administration replaced Judge Prado with Andrew Oldham, a former aide to Texas Governor Greg Abbott. Oldham, in his prior roles, had worked to restrict transgender Texans’ access to public facilities, promoted an anti-sanctuary cities law, fiercely advocated for discriminatory voting restrictions, and repeatedly litigated against women’s reproductive rights. Oldham also defended Texas’s so-called “TRAP” law, which sought to restrict abortions by requiring abortion providers to have admitting privileges at a hospital within 30 miles of where the abortion was performed.

The Texas TRAP law litigation is informative. The law was ultimately declared unconstitutional by the United States Supreme Court in 2016. The Fifth Circuit defied that ruling by upholding a similar TRAP law two years later. The Supreme Court was forced to strike down that law in 2020, but it just barely had the votes to do so: Justice Roberts joined the then-four liberal justices over the dissenting opinions of Justices Thomas, Alito, Gorsuch, and Kavanaugh.

Things in the Fifth Circuit could get much worse. Some of the full extent of the Trump nominees’ radical agenda is—just barely—being held in check by their slightly less conservative colleagues. For example, Judge Ho complained that the “[t]he Second Amendment continues to be treated as a ‘second-class’ right” after his colleagues narrowly voted to deny en banc review (a process by which the entire court reviews a panel decision by three of their colleagues) of a panel decision upholding a law banning the interstate sale of guns.

Sadly, when it comes to women’s reproductive rights, the radical views of the Trump appointees are already carrying the day. On August 18, 2021, in Whole Woman's Health v. Ken Paxton, the Fifth Circuit granted en banc review and overruled a panel decision that had, correctly, struck down a Texas law that banned a common procedure used for second term abortions. And with respect to the highly controversial SB8, the Texas law banning all abortions after six weeks and deputizing citizens to sue violators, the Fifth Circuit went so far as to intervene in a lower court proceeding. The Court’s highly unusual action prevented a trial court judge from even evaluating whether the law should be stayed pending litigation over its constitutionality.

Will the Supreme Court continue its practice of reversing the Fifth Circuit’s attempts to ban abortion? The balance on the Court has changed; early results do not look promising. Justice Roberts again joined the remaining liberals on the court in voting to stay SB8, but he was unable to get any of the court’s now five other conservatives to join. Three of those conservatives were appointed by Trump. And so the Supreme Court sat silently by, while the state of Texas effectively banned a constitutional right.

Interview

This interviewee worked as a counselor in an abortion clinic in Louisiana in the early 1980s.

How did you get to be a counselor at an abortion clinic?

I had a B.A. in Psychology and it was one of the few jobs I could get with that lowly degree.

What were you doing in Louisiana?

My husband was building gas pipelines; we were following the oil.

Were you pro-choice?

Um… yeah. I had to come face-to-face with the reality of what abortion was, and I was and am pro-choice.

What was the face-to-face reality like?

The clinic where I worked was in a house. I’ve had encounters with anti-abortion protestors, but I don’t remember them being there. I don’t remember there being protestors there.

The house had, maybe, five rooms set up for surgery, and other rooms set up for recovery. The processing unit was in the kitchen. I saw graphic things in that kitchen that weren’t always comfortable for me. Still—the work they were doing in that clinic was heroic. I thought so then, and I think so now.

Some of the people I worked with, the people who answered the phones, were very young. I remember them being stoned, trying not to laugh when a woman called yelling, “It didn’t come down this month—it didn’t come down!”

The place was not perfect.

But the women who came to us were desperate. They’d come in, weeping—they’d have a few kids already, could barely get by. They couldn’t have any more kids, didn’t want any more.

What happened for someone who wanted an abortion?

Well, she’d call in and set up an appointment. We used cautious, non-emotional language when we talked about things, careful not to upset anyone. A one-day procedure cost, I think, $200. I remember more clearly that the two-day procedure cost $400.

What was the difference between a one-day and a two-day procedure?

I think the one-day procedure was termination of pregnancies up to 10 or 12 weeks, and the two-day procedure was terminations after 16 weeks. I think the doctor at that clinic, after I worked there, was sued for providing late-term abortions illegally. I don’t remember what happened—my ex-husband might remember.

What happened on the day of a person’s appointment?

First, she’d talk to me, and I’d make sure this was what she really wanted. I’d be tippy toeing around words, very dry, very technical. Mostly, people did want an abortion. The doctor called the highly emotional patients PITAs—pains in the ass. Once, I was speaking to a Catholic woman, very emotional, who asked if she could have some fetal blood to put on her forehead afterwards. She would have been called a PITA. If someone was highly emotional, I’d share that information with the doctor, but generally, the interviews were straightforward.

Did the Catholic woman get the blood?

Oh no. Definitely not.

So, what happened after an interview with you?

Well, the procedure took 45 minutes, if that. Then the patient would spend two or three hours in recovery, being watched, to make sure her bleeding was normal. Then, when she was safe to go, that was that.

How do you feel, four decades later, when you think about your time at the clinic?

It wasn’t perfect. But regardless of my feelings of concern about the kitchen, or the stoned workers, the medical staff there were doing heroic work. Most of the people who left that clinic left sighing in relief.

Focusing/not focusing on/in the weather. Rain on concrete and some courageous strawberry runners, Seattle, Washington, U.S.A. 2021.

* The title of Issue 035 is a quote from Audre Lorde’s Zami, A New Spelling of My Name.

The editors of Behind a Door are particularly grateful to the contributors of Issue 035 for sharing their personal experiences regarding one of their and our Constitutional rights.

Need Abortion is a Know Your Rights campaign with links to various legal, medical, and financial resources for those in Texas seeking access to abortion, and for people who want to support access to this Constitutional right.

Make art and/or writing. Send it to info@behindadoor.com. We will publish submissions in this ezine or in our first limited edition handbound chapbook.

Wow, this was beautifully and exquisitely presented. I love the way everything flowed. I especially appreciated how one woman referred to killing a fish and that there was a fish mobile in the next story. Very, very well done.