Leaving logic.

033

Art

Leaving Logic

K. Harkins

Leaving Logic, completed in 2019, is about the important contemplations that take place when I am truly doing nothing. Contemplations that lead me to question received wisdom, what is thought of as "given," as not logic I subscribe to. This is a delightful feeling and promotes giggling.

It is 40” wide x 30” high. The work is on canvas and its media include fabric, spray paint, markers, and a photo I took of a bush.

Leaving Logic has been shown at Columbia City Gallery and Core Gallery, both in Seattle.

Recollection

Congratulations!

C. Hudak

Twenty years ago this summer, I got knocked up by a guy I barely knew. At the community clinic where I went to confirm the drugstore test results, a nurse breezed in with a sunny smile. “Congratulations! You’re pregnant!” I crumpled in a flood of tears. The nurse left me alone to weep. As I slowly regained myself, I thought, “Well, at least she probably won’t make that mistake again.”

I quickly came up with a plan. I’d reserved a spot at a writing retreat months earlier, because I was 25 years old, a writer, and wasn’t sure what to do with my life. My plan was: go to the writing retreat; figure out my life; come home; have an abortion; get on with my life. At the retreat—a silent, Buddhist writing retreat that began on September 11, 2001, and is a story for another time—the only thing I figured out was that I would not, in fact, have an abortion.

I came home. Given the totality of circumstances (another story for another time), I knew I would be raising this baby by myself. I’d heard a college degree could contribute to a higher salary, so I registered for classes at Seattle Central Community College. A friend offered me a part-time job running a miniscule non-profit; I took her up on it. I continued temping at Microsoft, too, mostly writing content for Flight Simulator.

A colleague said, “How will you do this?” and I said, “What do you mean?” He said, “You can’t raise a baby by yourself.” I laughed. Of course I could. I was about to become a third generation single mother.

At the hospital, a nurse named Theresa put a little machine on my little belly, and I heard the baby’s quick little heartbeat for the first time. I squinted as the light in the world changed color. Theresa also explained that I would be having a high-risk pregnancy. Me and Theresa began seeing a lot of each other.

I didn’t vomit too much, but I fainted a fair bit. Weekdays, working at Microsoft, I was obsessed with fried egg sandwiches and canned peaches from the cafeteria. I ate them for breakfast and lunch, though occasionally, instead of eating lunch, I closed the blinds to my office, curled up on the floor beneath my desk, and slept for an hour. Weekends, on breaks from working at the tiny non-profit in the University District, I ordered, exclusively, saag aloo and mango lassi from the Indian restaurant at 42nd and the Ave. The woman who brought my meals said, “Your baby loves our food so much. Make sure you bring her to meet us.” During evening classes at Seattle Central, my new friend, Chris, who used a wheelchair, pointed and stared when the baby visibly rolled beneath my skin nearby his eye level.

I gathered a birth team: my closest female friend, an ex, my alcoholic brother, and my two favorite neighbors. None of them quite knew what their role was, but neither did I, so it seemed fine. My neighbors came to birthing classes with me. My ex brought pregnancy books. Late at night, perusing them, I got so overwhelmed by constant mentions of a pregnant woman’s partner that I hurled the books against a wall.

Concerned that I would hate my baby, I began seeing a therapist. I hoped she might provide me with tools, so that when I hated my baby, I could still be a kind mother. The therapist was a thin woman with a pristine bob and excellent posture. For a few weeks, she listened to my stories about the various dysfunctional relationships in my life, as well as my concerns about hating my baby. She gently encouraged me to set some boundaries. I thought she was well-intentioned but clueless until, one day, she rocked my world.

“Did you know that most mothers love their babies?”

I did not. I sincerely doubted, in fact, that the therapist was correct, but her firm assertion exposed a distant, scarcely discernible light of possibility.

Eventually, I was put on bed rest. I didn’t have a television, so I stayed at my ex’s place and self-soothed with Genevieve Gorder. I read P.G. Wodehouse and took myself on long, ill-advised walks between the University District and Capitol Hill, occasionally stopping to lick a rock along the way.

Labor began on a Sunday night. The ex and I went to the hospital, where someone examined me and said, “Congratulations! You’re in early labor. Go home, have a snack, take a shower, get some rest, and come back in the morning.” Back at his place, my ex peeked at me in the shower. “You’re very beautiful right now.” I told him to fuck off. I went to bed, expecting to see my baby soon.

Ha.

Nothing much happened on Monday. On Tuesday, my brother accompanied me to a previously scheduled appointment. Theresa looked concerned. She went away to run some tests. When she returned, she said, “Congratulations! You’re having a baby! Today. Right now. If you don’t, you might die. Get into this wheelchair.”

Theresa rolled me up to Labor and Delivery. The rest of the birth team arrived. The doctors prescribed Pitocin and whatever they give eclamptic women to keep them from having seizures and dying during labor.[1] I began vomiting a lot. Someone put on the playlist I’d made, which made me want to burn the hospital down, so we turned that off. Someone drew a bath, but as soon as I lowered myself into the tub I wanted to die, so I got out as quickly as my dripping wet, laboring, pregnant body would allow. (And that was the end of the birth plan.)

The Pitocin didn’t work. Tuesday rolled into Wednesday, which rolled into Thursday. Nurses came in and out, wondering which of the men from my birth team was the father. “None of them is the father,” I said. “There is no father.” Every time a new shift started, I said it again.

I learned several new medical terms. They tried something called Cervidil, to make my cervix open, and like the Pitocin, it didn’t work. On Thursday night, they decided to break my water. I said, “You will need to give me an Epidural, because even though I planned to do this without one I am very, very tired and will take any assistance I can get.” They said the Epidural lady would be a minute, so someone brought me a mango lassi, which I snuck one sip of before the Epidural lady promptly arrived and took it away. She stuck the needle in my back, and I went to sleep.

You must know by now: the Epidural didn’t work. I woke, in the middle of the night, in insane pain. I kicked at my ex, who was sleeping on a couch nearby. “Get the fucking midwife, right the fuck now.”

People had admired my good humor over the course of the week—even with all the anti-convulsants, vomiting, and pain from near-constant, dull contractions, I never forgot a please, thank you, or I’m so sorry (for all the vomit). Those manners were now cast aside. When a midwife I hadn’t met before came in and roughly examined me, I explained that her intense inspection wasn’t fucking necessary as I was now OBVIOUSLY in active labor and she should just get a fucking doctor because this was a high-risk pregnancy, for fuck’s sake.

A doctor arrived. My brother arrived. My brother told me, later, the hardest part was hearing me whimper between contractions. I don’t remember whimpering. I remember my ex and my brother telling me to “wait to push” and thinking they were the stupidest people I’d ever known. I remember several doctors, each trying different things. One was very good-looking; another reached in with enormous forceps and leveraged herself by placing her foot against the birthing table beside me.

Nope. Nope, nope, nope. The baby was not coming.

“Would you like to have a c-section?”

“Jesus Christ—whatever you think is best.”

My ex leaned in and whispered, “Tell them you want a c-section.”

“FINE. GIVE ME A C-SECTION.”

Approximately ten minutes later, I was in a very cold room surrounded by new nurses and doctors, when I heard a baby screaming. Someone said, “she’s not even out yet!” Someone took a picture of a moment later. The baby being raised from my body looks irate at having been removed from the womb.

Someone wrapped up the baby and brought her beside me. I learned, just then, that my arms were bound to the operating table.

“Does she have all her fingers and toes?”

“She does.”

“Well then, someone else is going to have to deal with her for a little while, because I am exhausted.”

I don’t know how long I slept. Did I properly meet my daughter on Friday, or Saturday? I have no idea. When I woke, someone brought the baby and rested her on my bare chest. She wriggled, on her own, to my breast.

Time, and light, and knowledge were never the same again. Until that moment, I had no idea that babies arrive whole—this baby was a complete person, intact and sound. It was utterly clear that my task was to protect and defend this new person’s wholeness. I didn’t love the baby yet—I hardly knew her. But I was certain that if anyone (ever) attempted to harm her, I would tear their arms from their bodies so I could use their own limbs to beat them to death.

Me and this baby, my baby, stayed in the hospital for a few days. I didn’t begin to recover until they gave me a blood transfusion, at which point I repeatedly told anyone who would listen, “Now I understand why Keith Richards got all those blood changes!”

On Monday, they set us free. I stood in the spring drizzle with my baby plonked in the navy blue carseat my Microsoft colleagues had bought her. While we waited for our ride home, a stooped old woman wearing smeared, neon pink lipstick leaned down toward the carseat.

“Where is her hat?!”

I peered where the woman peered.

“Oh,” I said, as if the woman had lost the hat herself, and I was helping her search for it. “It’s right there.”

“Put the hat on the baby! It’s cold outside!”

The baby seemed fine to me, but I was too tired to protest. I put the hat on the baby.

The woman raised a crooked finger and pointed at me. “You will be a terrible mother,” she croaked, which cracked me up.

“You might be right!”

When my neighbor arrived in her turquoise pickup, the little old woman was gone, and I was still laughing.

[1] Downton Abbey Spoiler Alert: I was unaware of the full effects of this experience until, years later, I watched Lady Sybil die after giving birth. I sobbed, and sobbed, and sobbed.

Art

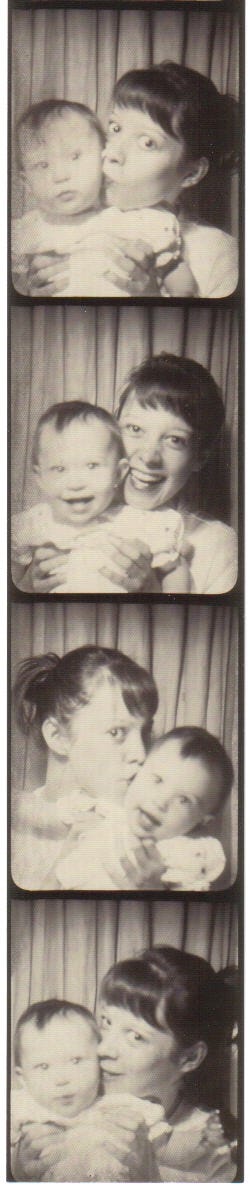

To Hold

I. Vega

Poem

First-grade math

S. Pai

my six-year-old’s brain

is broken by the equation

❤️ + 3 = 14

to solve for heart

sub an X like a treasure

map, his father gives

an analogy with cookies

as I observe the confusion

multiply in my son’s speech

b/c love is another language

b/c heart is not a fixed number

b/c my love for you is infinite

Republished with permission from Empty Bowl Press. First appeared in Virga, which was just released by Empty Bowl, and is available here.

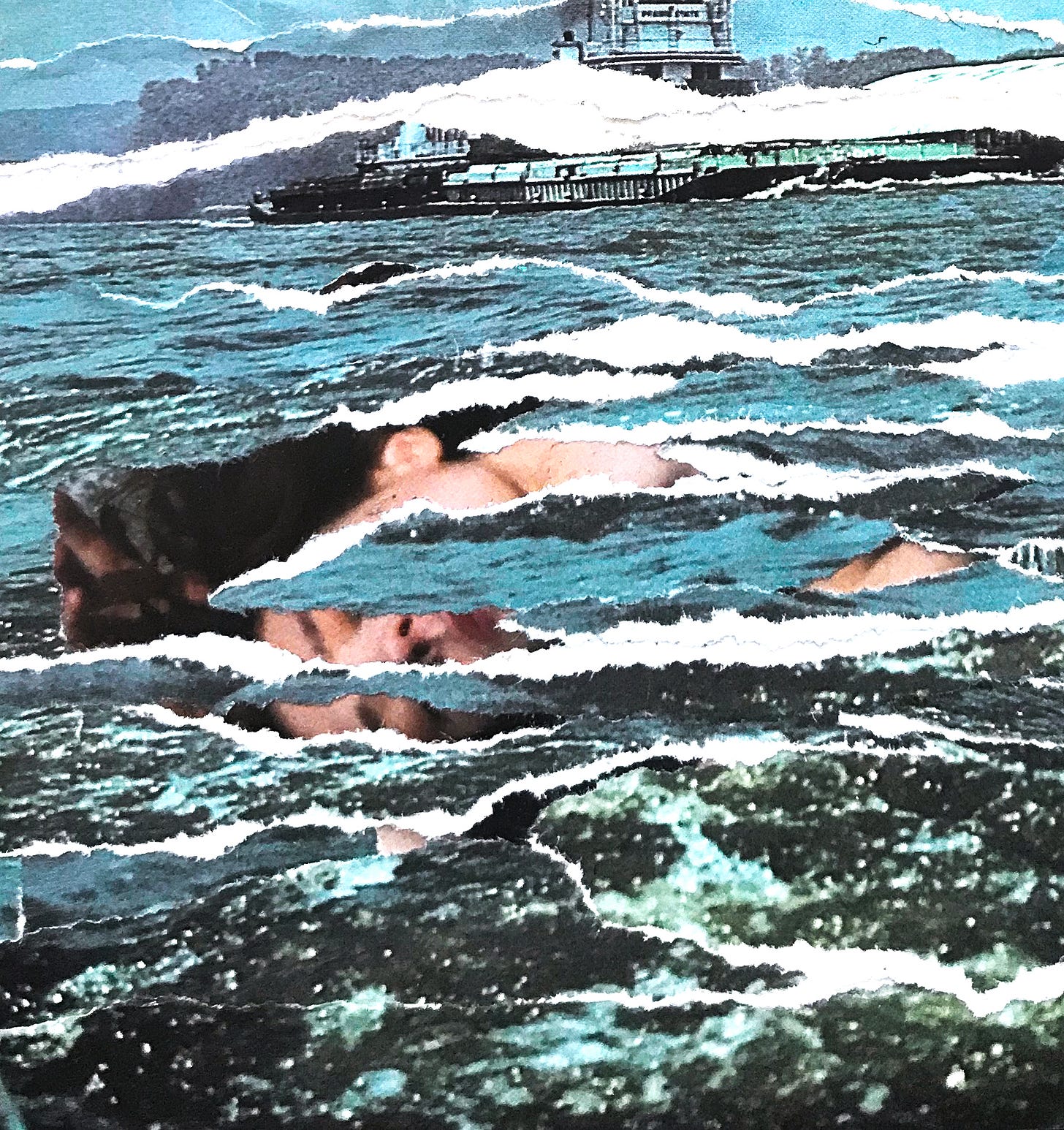

On a dark day, a child seeks her balance in the Salish Sea. Tofino, British Columbia, Canada.

Make art and/or writing. Send it to info@behindadoor.com. We will publish submissions in this ezine or in our first limited edition handbound chapbook.